Astrophotography in India - I

Astrophotography in India - I

Introduction

“tapasā

cīyate brahma tato'nnamabhijāyate |”

The above mantra from the Mundaka Upanishad (Verse 1.1.8) has been translated variously by many scholars, but in lay terms it can be read as - the Universe expanded due to the force of Brahma’s ‘tapas’ and then came food/matter. It is now understood, that following the Big Bang, matter in its present form was created as the universe cooled down, creating stars and solar systems and other objects that we encounter today. From our vantage point on Earth, the night sky provides a window to the common man to peer back into time and observe the majestic creations that lie strewn across the ever-expanding emptiness of space. Photons emerging from these majestic celestial objects, travel vast distances to reach our dear planet and illuminate our minds.

My love for science and technology was kindled by the soft light of the stars on which I could gaze for hours as a child. As an adult, my professional work in the area of fluid mechanics makes me naturally interested in fluid mechanical phenomena at a universal scale, and what better way to explore this idea than through astrophotography. In practice, astrophotography is imaging of portions of the night sky and the object of interest can be either belong to the solar-system or lie outside of it. Depending on the object of interest, astrophotography is typically classified as:

•

Landscape

•

Planetary or

• Deep-sky

You might have already come across landscape astrophotography in the form of beautiful wide-angled images of milky way set across a mesmerizing Earthly background. Planetary astrophotography, as the name suggests, deals with objects within our solar system such as the Moon and the planets. In contrast, deep-sky astrophotography leaves out objects inside the solar system in favor of objects outside of it. My favorite deep-sky astrophotography objects are nebulas – vast clouds of luminous gas strewn across sometimes thousands of light-years – they are brilliant examples of inter-stellar fluid mechanical phenomena. Photographing these objects, while thrilling, can also be enormously difficult. Other oft-photographed deep-sky objects are galaxies, star-clusters and supernovae.

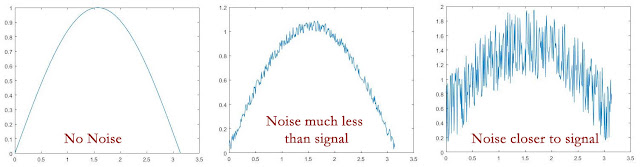

Astrophotography, as compared to other forms of photography, has its own unique challenges due to the very poor signal-to-noise ratios and the high optical magnifications that are required. However, even within astrophotography its various forms can their own requirements. The object of interest – whether it’s a planet or a nebula – becomes the determinant of the technique and difficulty level. Photography, after all, is just a matter of optics and the way we exercise control over optics is through our camera settings. Capturing planetary bodies often boils down to necessary optical magnification; otherwise such imaging is fairly straightforward. Several applications are available, which allow you to locate the planets in the night sky accurately. Landscape photography with Milky way can similarly be straightforward. From a dark-enough place, away from the light polluted cities, you can even see the Milky Way with your eyes only. The Bortle scale is used to quantify light pollution and a Bortle Scale 1 or 2 location is ideal for seeing the Milky Way with naked eyes (see Figure 1). Compared to landscape or planetary astrophotograhy, deep-sky astrophotography is the most challenging. The objects are not only distant, but also incredibly faint ! Vast clouds of gas strewn across light-years of space, lit only by photons of distant stars or galaxies that are separated from Earth by ghastly distances (think millions of light years) – these objects make the life of a deep-sky astrophotgrapher’s challenging but also very interesting. It is probably no surprise that deep-sky astrophotography is considered the most difficult of the three types of astrophotography. In this essay series, we will be focusing on deep-sky astrophotography.

Deep-sky objects are not part of any constellation, yet for ease of navigation, they are often associated with constellations. There are a total of 88 constellations in the night sky. These are divided into northern and southern hemispheres with the celestial equator running close to the Orion’s belt. Depending upon your locational latitude you may be able see only a few of these constellations. Due to our location (i.e. India) being close to equator, we have the advantage of being able to see both the northern and southern hemisphere constellations. Do not panic if you are a novice with regards to constellations – technology will come to your rescue. Just download an app like stellarium and point your mobile phone towards the night sky to locate the deep sky objects you wish to capture.

Deep-sky astrophotography is a geek’s golf ! You can start off with simple gear; but cost of hardware climbs very steeply with ambition. Also, like golf, this hobby is for the patient learner – it can take weeks, months and even years for a novice to learn all the tricks and I won’t recommend it to men or women in a hurry. On a good day, one can get several good shots and then there are times (e.g. monsoons) when entire weeks can go by without clear skies. If you are a resident of an Indian megacity, city light pollution and PM2.5 levels can also play spoilers. I live in Bangalore – one of the fastest growing metropolitan areas of India – and deep-sky astrophotography from such an extreme light polluted area has made the enterprise challenging. Yet, navigating this challenge has provided me with an amazing insights into skills required for cultivating expertise in this area. Deep-sky astrophotography requires one to have a degree of understanding of optics, imaging and image processing. Better your understanding, better you can understand the thumb-rules and work out your own job-flow. Finally, there is an element of art involved here as aesthetics plays a role in what images you will churn out. This blog in intended to help the un-initiated dive into this enterprise.

This blog I will be co-writing with my friend Vyom. Vyom is also a deep-sky astrophotography enthusiast and had been working on this by himself, till we discovered that we have this interest in common. We decided to join forces and the outcome has been quite spectacular – along with a steeper learning curve, we have been able to aide each other in their strengths. This blog is an enterprise into documenting our work not just for ourselves, but for other deep-sky astrophotography enthusiasts. We will outline not just the path to get to beautiful and brilliant images, but also the way to avoid common mistakes/issues. One specific issue we hope to highlight are the challenges of imaging from a megacity.

Figure 1: Milky Way as captured by Vyom from Maldives (Bortle 2) in May 2022.

नक्षत्राणां ज्योति: मन: प्रचोदयात्

May the light of the stars illuminate your mind

AK dedicates this series of posts to Annapoorna.

About the authors: (First) Aloke Kumar is

currently an Associate Professor at Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. He

tweets at @aalokelab

(Second) Shubhanshu Shukla is an amateur astrophotographer.

*'I' in an article refers to the first author of that article

Opinion/views expressed are purely personal and do not reflect the opinion/views of employers.

Comments

Post a Comment