Poorna from Poorna: A Repeating Motif

Poorna from Poorna: A Repeating Motif

In the

previous essay, we saw that the Upanishadic mantra (पूर्णस्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते)

encodes a mathematical relationship that is consistent with the property of

infinities. Since Upanishads were conceived long before modern

understanding of infinities and their paradoxical properties, it behooves us to

explore deeper on this issue. Were the authors of the Infinity mantra1 aware of its profound implications or was this a mere

co-incidence2? Even worse, are we reading too much into a simple

mantra and imagining relationships that do not exist? A rigorous discussion of

this issue must tackle these questions.

Ancient India or

Bharat is said to have had a strong culture of inquiry and a very rich landscape

of scientific thought. On closer observation one finds that the philosophical construct of the Infinity mantra is not an

aberration, but rather a repeating motif throughout various aspects of Hindu

Jeevan Darshan3. These

repeating motifs are strong circumstantial evidence suggesting that the Bharatiya4 tradition truly

attempted to understand the infinite. In this essay, I have chosen four of

pieces of ‘circumstantial evidence’ that suggest that the contemplation of

infinity was not restricted to the Upanishads, but rather an important aspect

of a philosophically and mathematically advanced civilization.

1.

Multiplicity of deities

In the

last essay, we understood the conundrum of poorna from poorna through a countably infinite set.

However, the same may be applied towards uncountably infinite sets. In the

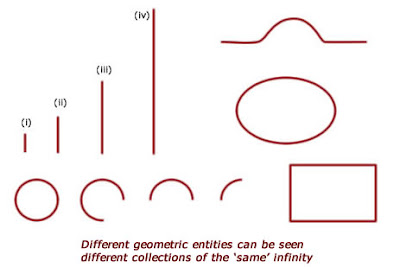

figure below, the line segments (i)-(iv) are all of different lengths. Yet, all

these lines can also be seen as an infinite collection of points and from this

perspective, all line segments represent equivalent (uncountable) infinite

sets. Same is true for all the different geometric shapes shown. In the sense

of collection of infinite points, they are all equivalent or 'same'. At the

risk of offending some mathematicians, we can say that the same infinity

represents itself as different physical entities. The mathematically inclined

reader would immediately realize that this is just an alternate form of the idea

that you can take poorna from poorna and still be left with poorna. Others can try

that as a homework problem.

The

above diagram is also key to understanding the astounding multiplicity of

deities in the Hindu pantheon. Take the example of the Dashavatars or the ten Avatars

of Shri Vishnu. The avatars are usually represented as a temporally ordered

set, yet there is no hierarchy within them. The Krishna avatar is neither

superior nor inferior to the avatar Rama. Also, none of the ten avatars are

greater or inferior compared to Vishnu himself. All the avatars are seen to be

equivalent to each other and this equivalence is an affirmation of the concept propounded

by the Infinity Mantra. When Shri Vishnu incarnates in the human form as Rama,

he does not become deficient in any form and nor is the incarnation deficient

in any form. Same is true for the different rupas

of Shiva. Thus, we see that the Shanti Mantra under discussion encodes a

philosophy that reverberates through the Puranas (पुराण)5.

2. Fractal temple architecture

The

idea that the entire ब्रह्माण्ड (Brahmanda or cosmos) is essentially a

self-repeating entity has informed Hindu temple architectures6. Rian

et al.7 analyzed the architecture of Kandariya Mahadev temple (1030

AD) at Khajuraho and found that its architecture was fractal in nature, and

this unique architecture resulted from the synthesis of Hindu cosmology and

philosophy as applied to temple design. In a typical fractal structure, a

singular geometric unit is repeated ad

infinitum by the making copies of the unit geometry and by reducing

its size successively. The figure below shows a fractal known as the Sierpinski

carpet, which is created by taking a square and then removing successively

smaller squares from the ‘unit’. Fractals such as this can have paradoxical

properties such as having a finite area, yet have an infinite periphery. We

must note that fractals are regarded as a modern 20th century

mathematical discovery.

Thus

any unit of the fractal is a copy of the main unit, an idea that is known as

self-similarity. In the context of the cosmos, the geometry is meant to denote

that the atman (आत्मन्) is a self-similar copy of the ultimate Brahman (ब्रह्मन्). This

idea is also the reason why poorna is associated with the ultimate Brahman (ब्रह्मन्).Thus we see

that the pursuit of infinity and its representations, was not limited just to

philosophy in Bharat, but was also applied to engineering practises of the day.

Such ideas would have required not only brilliant artisanship, but also complex

mathematics essential to civil engineering. Interestingly, ancient Indian rock

art (~

40,000 years before present) featured repeated tessellations, which professor

Subash Kak points out to be unique to the Indian tradition8.

3. Massive length and time scales

in Hindu cosmology

If the

underlying thought process is mathematical for a civilization contemplating

infinities, then one would expect the civilization to have dealt with large

numbers also. Massive numbers are something that Bharatiya tradition has had a long familiarity9.

Massively large numbers were part of the early Vedic literature, where names

were assigned for all multiples of ten up to 1018. Still larger

numbers are found in the Ramayana which has terms all the way up to 1055.

Some of these large numbers are used to denote time-scales. Hindu, Buddhist and

Jain texts all contain references massively large cosmological time-scales9.

Even spatial length scales in Hindu texts are extremely large. For

example, distances from Earth to Sun are usually of the order of millions of

yojanas8. Professor Amartya Kumar Dutta, a noted mathematician,

states that "Expressions of such large numbers are not found in the

contemporary works of other nations"9. Interestingly, whether the large time/spatial scales are correct or not is immaterial to the question at hand. The very conception of such large numbers is a fascinating development in itself.

These

developments are not stand-alone. Methods, which would become precursors of

modern mathematics, were devised to allow the rishis to work with numbers and employ them in different aspects of

life. In his book ‘Computation in Ancient India’, professor Subhash Kak states

that "We find that the ancient Indians were greatly interested in

computing methods in geometry, astronomy, grammar, music and other fields”8.

A complete review of mathematical techniques used in Ancient India are outside

the scope of this essay, and enthusiastic readers can refer to specialized

texts to pursue in-depth understanding of mathematical traditions of ancient

India8,10. Rounding up on this topic, we find that not only did the Bharatiya culture obsess with infinity, they also dealt with very large numbers. This indicates that the bedrock of the civilization had a strong mathematical element to it, and that the contemplation of infinity was not superficial in nature.

4. The Bindu

Not only

did the ancient Indians contemplate on the nature of infinity, they also

contemplated on its anti-thesis – nothingness. The ubiquitous Bindu is the living fossil of this long

contemplation and it finds an expression not only on the forehead of Indian

women, but also in the Shri Yantra (see Figure). Yet, the Bindu’s impact on

humanity occurs through the Bindu being

used to in the decimal system. Bindu or the dot was the earlier symbol used in

ancient India’s mathematical calculations, which later on gave way to a small

circle, the chidra11. Yet,

hundreds of years before it use in the decimal system, the philosophical idea

of shoonya can be traced to the

Rigveda’s Nasadiya sukta. The suktam contemplates on the creation of

the universe itself, and states that there was a time, when there was no

creation. There was no Earth, no space, no water and there was only nothingness

– The Mahashoonya or the great zero. We

at this stage, remind ourselves that in a mathematical sense poorna can

imply both shoonya and anantah (infinity)12. The concept of Mahashoonya preceded the mathematical shoonya - the later probably being one of the definitive giant leaps by the human civilization.

Conclusion

We reviewed motifs from disparate parts of the Hindu religious expression, to show how deeply ingrained the pursuit of infinity is the dharmic philosophy. In the interest of keeping this essay short I did not touch upon certain philosophical schools of Hinduism such as Yoga and Vedanta. The keen observer would find that the Infinity mantra reverberates in those schools as well. Thus, the Infinity Mantra encodes a fundamental philosophy of the Hindu Jeevan Darshan. As a corollary, we find that that complicated mathematical and philosophical ideas are at the base of Hindu thought.

References

& Notes:

1. The

following mantra is referred to here as the Infinity mantra:

ॐ पूर्णमदः पूर्णमिदम् पूर्णात् पूर्णमुदच्यते |

पूर्णस्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते ||

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ||

2. Upanishads

do have commentaries, but they are by later rishis and gurus, and most of these

commentaries are spiritual in nature and do not ponder much over the mantra's

mathematical nature.

3. The

Hindu perspective on life

4. Bharatiya word is used as a synonym for Ancient

Indian.

5. Genre of Hindu literature containing kathas (stories) of creation and of

various avatars.

6. Trivedi, Kirti. "Hindu temples: Models of a fractal

universe." The Visual Computer 5.4 (1989): 243-258.

7. Rian, Iasef Md, et al. "Fractal geometry as the synthesis of Hindu cosmology in Kandariya Mahadev temple, Khajuraho." Building and Environment 42.12 (2007): 4093-4107.

8. "Computation in

Ancient India", Editors T.R.N. Rao and Subhash Kak, Mount Meru Publishing,

Ontario, Canada (2016)

9. Dutta, Amartya Kumar. "Mathematics in ancient

India." Resonance 7.10 (2002): 6-22.

10. Yadav,

Bhuri Singh, and Man Mohan. Ancient Indian leaps into mathematics.

Birkhäuser, 2011.

11. Bäumer, B. "Kalātattvakośa: A Lexicon of Fundamental Concepts

of the Indian Arts. Vol. 2: Concept of Space and Time." 399-428.

12. Previous essay – Poorna from Poorna: Is that possible? By AlokeKumar

Acknowledgements: The author thanks Prof. Subhash Kak (LSU, USA) for his inputs.

About the author: Dr. Aloke Kumar is currently an Assistant Professor at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Twitter handle: @aalokelab

Comments

Post a Comment